The U.S. economic picture is looking more muddled than expected. The Consumer Price Index rose 0.8% last week. Used automobile prices rose quickly in response to the semiconductor shortage limiting new car production and demographic trends boosting demand. Retail sales were expected to build on last month’s stimulus-led surge but instead were flat. Industrial production remained a bright spot, adding 0.7% last month as manufacturing demand remained strong.

Key Points for the Week

- S. consumer prices surged 0.8%, supported by price increases in autos and other reflation trades.

- Retail sales were flat and missed expectations for 0.9% growth as declines in general merchandise and clothing purchases cancelled out gains in motor vehicles and restaurants.

- Industrial production gained 0.7% and has surged 16.5% in the last year from COVID-led declines.

The number of open jobs rose to 8.1 million in March, providing additional evidence increased unemployment benefits are curtailing the available pool of workers. As the country steadily reopens, filling some of the 1.2 million open positions in hotels, restaurants, and similar industries will be important to fuel a sustainable recovery. Initial jobless claims fell another 34,000 to 473,000.

Markets were volatile last week. The S&P 500 moved by more than 1% in four of the five trading days. The S&P 500 slid 1.3% as the inflation surge unsettled markets and raised concerns about interest rate increases. The MSCI ACWI Index dropped 1.5% as declines abroad were slightly higher than in the U.S. The Bloomberg BarCap Aggregate Bond Index didn’t respond well to the inflation data either and dropped 0.4%. Bond prices fall when interest rates rise, and rising inflation can often lead to higher rates.

Chinese retail sales and industrial production will headline economic data released this week, and the Federal Reserve will release the minutes from its latest meeting. Given the big increase in U.S. consumer prices, similar data releases in the eurozone, United Kingdom, and Japan will garner extra attention.

Figure 1

Flexibility and Recovery

The NBA inducted three all-time greats into its Hall of Fame last week. Tim Duncan, Kevin Garnett, and the late Kobe Bryant were great even when compared to other members in the Hall of Fame. Bryant and Garnett both went straight from high school to the NBA and logged more than 55,000 minutes of game time in their NBA careers. Early in his career, Bryant admitted he invested “zero” time on flexibility and recovery. Ice baths and stretching weren’t part of his regimen. In his last season, at age 37, Bryant had a small army of trainers and medical personnel working with him to keep it going one more year.

Like NBA players, economies need flexibility, too. When flexibility is wanting, injuries occur more often. For NBA players, it means missed games. For economies, it can sometimes lead to inflation.

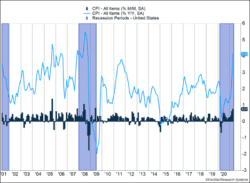

Last week, the U.S. inflation rate, as measured by the Consumer Price Index, rose 0.8% from the previous month and is now up 4.2% over the last year. Much of this jump was due to what statisticians call a “base effect,” which means the starting point for the data was influenced by special circumstances. In this case, prices for several goods dropped sharply during the initial stages of the pandemic. If you look closely at the bars on Figure 1, you can see a sharp spike lower, showing the decline in prices. One year later, inflation looks like it is jumping rapidly because it is being compared to a low point. Over the next couple months, the starting point moderates and the base effect will be eliminated.

But the base effect is only part of the story. The monthly increase of 0.8% is quite large. Sometimes big swings in inflation are caused by two of the more volatile elements: food and energy. But energy prices dropped last month, and food prices only rose 0.4%. Core inflation, which excludes those two areas, rose 0.9% compared to the previous month.

The impetus for rising core inflation came down to five segments that accounted for 0.57% of the 0.9% increase. The most notable segment was used cars, whose prices jumped more than 10% last month and accounted for more than one-third of the monthly increase in core inflation. Semiconductor shortages have curtailed the production of new cars while demand is rising as people move to less densely populated areas. The semiconductor market isn’t flexible enough to make up the shortages quickly, so the market has reacted by pricing used cars higher.

The other four segments were all related to travel and events. This group included car and truck rentals, airline fares, sporting event ticket prices, and hotels. Car and truck rental prices surged 16.2% last month. The other three were up between 8.8% and 10.2%. None was as impactful as used cars prices, but collectively they accounted for a 0.22% increase in core inflation. Flexibility also mattered here. All these areas have struggled during the pandemic and were not able to ramp up supply rapidly enough to meet increased demand.

The important question isn’t whether inflation will be high temporarily, but whether it will last. Our view is the economy should be able to adjust as long as government policies don’t curtail its flexibility. Inflation is sometimes defined as too much money chasing too few goods. With free-flowing stimulus money meeting supply constraints and only a partial reopening, prices spiked higher.

Long-term inflation is only likely to take hold if flexibility is taken away from the economy. Supply constraints in semiconductors and timber have pushed prices higher and affected many markets. Those prices should come back down as long as companies have the incentives to respond by increasing supply. If energy prices increase, energy companies need the flexibility to produce more. If the demand for labor is higher, policy incentives should not curtail the supply by paying people more not to work than they could make by having a job.

Prior to COVID, the U.S. economy had very low inflation, in part because it was flexible. Unless policies change, we expect inflation to move to between 2% and 3% in coming months.

—

This newsletter was written and produced by CWM, LLC. Content in this material is for general information only and not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. All performance referenced is historical and is no guarantee of future results. All indices are unmanaged and may not be invested into directly. The views stated in this letter are not necessarily the opinion of any other named entity and should not be construed directly or indirectly as an offer to buy or sell any securities mentioned herein. Due to volatility within the markets mentioned, opinions are subject to change without notice. Information is based on sources believed to be reliable; however, their accuracy or completeness cannot be guaranteed. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

S&P 500 INDEX

The Standard & Poor’s 500 Index is a capitalization-weighted index of 500 stocks designed to measure performance of the broad domestic economy through changes in the aggregate market value of 500 stocks representing all major industries.

MSCI ACWI INDEX

The MSCI ACWI captures large- and mid-cap representation across 23 developed markets (DM) and 23 emerging markets (EM) countries*. With 2,480 constituents, the index covers approximately 85% of the global investable equity opportunity set.

Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index

The Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index is an index of the U.S. investment-grade fixed-rate bond market, including both government and corporate bonds.

https://abcnews.go.com/Sports/kobe-bryants-day-process/story?id=35954618

Compliance Case #01035048